By Katie Waring, Graduate Resident

My Sherman Centre residency project begins with the premise that disabled stories matter. Disabled stories matter because disabled people—historical, present-day, and future—matter. Yet, documenting historical stories of disability can often feel like an impossible task: centuries of institutionalization, legal and social discrimination, and lack of acceptance mean stereotypes and normative ableist perspectives are entrenched in traditional archives or else archives erase disability altogether. When disability is represented, it is nearly always through the perspective of a nondisabled person. As Gracen Brilmyer asks, “How can we tell a history of disability…when there is little or no archival evidence or when the evidence that is presented is harmful, violent, or incomplete?”

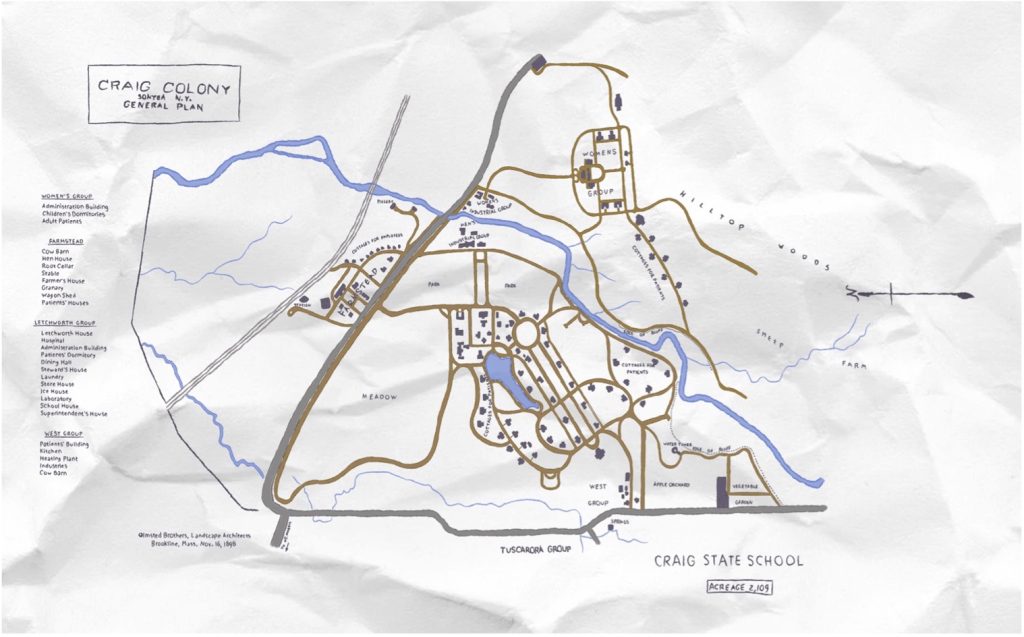

My PhD dissertation tries to tell the story of one particular institution and the people who lived there. New York State’s Craig Colony for Epileptics helped galvanize a eugenic movement: starting in 1896 when the Craig Colony opened and continuing through the first half of the twentieth century, the United States and, later, Canada incarcerated a rapidly increasing number of people with epilepsy and other physical and mental disabilities into “colonies”—institutions typically spread across dozens of buildings and surrounded by farmland worked by the patients. As the first such institution in the U.S., Craig’s policies and norms offer an example of how society’s perception of disability shaped—and continues to shape—lives: it was a place where medical staff viewed epileptics as inmates, not persons, and where neurological status constituted one’s identity, social status, and competence. Despite its prominent role in shaping institutional policy, however, the Craig Colony has virtually ceased to exist in the U.S. historical record. Searching through the colony’s records, I found very little to tell me who the patients were, what their daily lives were like, or how they felt about the colony and its staff.

In response to this erasure of disabled lives, my PhD will construct—in collaboration with survivors, their family members, and descendants—a digital community archive to serve as a public memorial to the individuals incarcerated at the colony prior to its closure in the 1980s. I plan to work alongside local advocacy organizations to locate survivors, talk to them about their experiences, and foreground their oral histories in the resulting digital archive. This public-facing website, which I will construct and code, will be the first archive to focus primarily on the experiences of people with epilepsy.

For the residency, I am working to build an interactive map of the colony to include in the digital archive. Because I had previously drafted a map of the colony for an earlier course (tracing over photos of archival maps in Adobe Illustrator; pictured below), I’m now focused on learning how to transform this version of the map into one that is navigable—where visitors are able to click on a building and learn more about it, or listen to sections of oral histories where survivors tell stories about a particular place within the colony through embedded audio. In building a navigable version of the map, I hope to add an interactive element to the website which allows visitors to better understand the scale of the colony and its impact (by seeing the number of buildings and their uses) as well as position stories about the colony in the places where they occurred.

By linking short clips from survivors’ oral histories to the place where they occurred on the map, I hope to curate a participatory experience for visitors to learn about disability history and make clear the ramifications of institutional violence on disabled communities. In doing so, I draw on the work of Michelle Caswell, who states that “archival endeavors should not be about documenting the past, nor even about imagining the future (as I have previously argued), but about building a liberatory now.” As such, this project asks: how does this lineage of segregation and institutionalization continue to affect disabled communities today? And what might redressing such historical trauma look like? In building a digital map of the colony, I consider how thinking with the land may offer an alternative to archival erasure—and how researchers may return to the origin of historical violence to search for traces of stories and individuals erased from the official record.

About Katie Waring

Katie Waring (she/her) is a multimedia writer and third-year doctoral candidate in the Communication, New Media, and Cultural Studies program. Her research looks at the potential for community-engaged digital storytelling in highlighting suppressed histories. She holds an MFA in nonfiction writing from the University of Pittsburgh and her creative work has been published in literary journals such as The Normal School and American Literary Review, among others. She originally hails from New York.

During her Sherman residency, Katie aims to develop a navigable map which will be featured in the digital community archive she is curating for her dissertation. As part of her research, Katie is interviewing survivors of New York State’s Craig Developmental Center (also known as the Craig Colony for Epileptics) to construct a digital archive which centers patient testimony. As the first such colony for disabled people in North America, the Craig Colony helped galvanize a eugenic movement and promoted the segregation and sterilization of disabled people deemed ‘unfit’ for normative society. The digital archive aims to draw more public and academic attention to Craig’s historical importance through survivor-led testimonials, as well as serve as a public memorial to victims of institutional violence. The map will help visitors to the archive understand the scale and scope of the colony, as well as locate archival stories within their place-based context.

References

Brilmyer, Gracen. “Toward a Crip Provenance: Centering Disability in Archives Through Its Absence.” Journal of Contemporary Archival Studies, vol. 9, 2022, pp. 1-25.

Caswell, Michelle. Urgent Archives: Enacting Liberatory Memory Work. Routledge, 2021.

Leave a Reply