John Fink has been the Sherman Centre’s beloved Digital Scholarship Librarian ever since the Centre opened in 2012. In his tenure at SCDS, John has supported dozens of projects on everything from musical apps to biometric sensors. Get to know the glue that holds SCDS together with this quick Q&A.

SCDS: Take us through a day in the life of a Digital Scholarship Librarian.

JF: Oh gosh, there is no typical day! Even before pandemic times, I had *very little* do-this-task-at-this-time-of-day-each-day type of work. When I first became a librarian, I was a reference and liaison librarian so I had quite a lot of structure – every day spend x hours on reference desk, attend departmental meetings, things like that. My work as a DS librarian is more or less split between known, mid-to-long-term projects and occasional emergencies or urgent tasks that pop up.

SCDS: How did you get interested in digital scholarship? Where would you suggest emerging scholars and community members get started with DS?

JF: I was always prepped to be interested in digital scholarship / digital humanities as a sort of by-product of having a humanities background (of a sort, if you count an English degree focused on creative writing actually part of the humanities) coupled with a longstanding interest in technology. I can’t think of any shortcuts or bootcamp type stuff that will really give people a grounding in DS work; it’s so multifaceted and expansive that it just seems foolish to try.

My recommendation would be to find something that is digital scholarship-esque that you are really, honestly, truly interested in – I find that I *cannot learn something* above a very basic complexity just by saying “OK, I’m going to learn this thing.” I have to have a personal or work project that is somehow related to it in order to motivate myself.

SCDS: What’s something you wish more people knew about digital tools and digital scholarship? This could mean shouting out an underused resource, sharing a tip, venting about a common mistake, or something entirely different.

JF: That the “digital” is rapidly becoming meaningless, or at least quite a bit less important than it would have been a decade ago. Digital Scholarship to me broadly means doing “scholarship”, which I’m not quite sure what that really *is*, using digital methods because using non-digital methods would be too time consuming or impossible.

This last bit is important because, say, writing a paper on a word processor vs. writing it out by hand *is* using digital tools to do scholarship, but not to the point where it would be impossible to do non-digitally. Whereas the sort of classic example of digital scholarship, something like doing analysis on an *extremely large* corpus, like the Old Bailey Proceedings, you could not do (or it would be just a massive waste of time) simply by reading every proceeding yourself.

So going forward, the data we work with is likely to get more complex, and I imagine that the “digital” part will become more implicit and less directly references as everybody will be a “digital” scholar in some way or other.

Find a technological thing that interests you – not something you want to do for money, or because it will help you in your job or something. Something that you personally like.

John Fink on how to get started with DS

SCDS: You have a humanities background, then moved into the world of DS. If you had to persuade someone who was hesitant to explore tech to give it a chance, what would you say?

JF: Find a technological thing that interests you – not that you want to do for money, or because it will help you in your job, or whatever. Something that you personally like. Make sure it’s not a huge thing, but not that small either – something that will take you a little bit of time but has identifiable steps or goals that can be achieved so you know you’re making progress. Make sure you have a *sandbox* of sorts – that is, if things go completely sideways you don’t break something important and perhaps more importantly you don’t look foolish in front of other people.

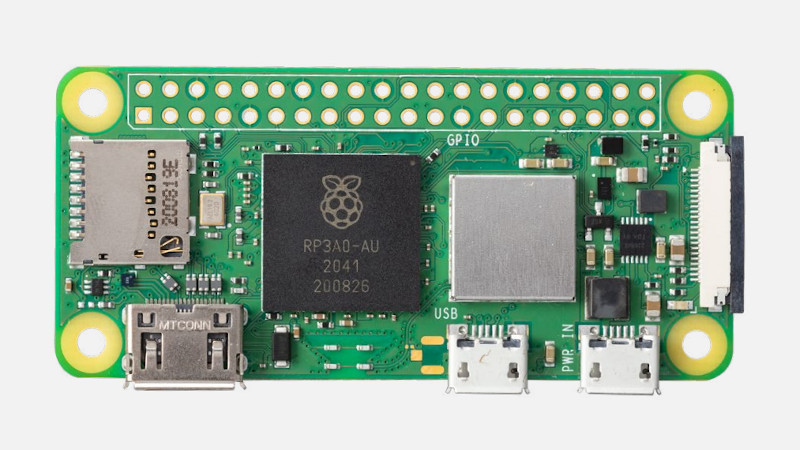

Let’s take an example I know something about and say you’re interested in how Linux works but know nothing about it. You could do something like purchase a Raspberry Pi Zero 2 W (about twenty bucks for the computer itself, if you don’t have a memory card or power supply around could run you up to 50 maybe), follow the basic instructions to get an operating system on it, and then just… poke around. Interested in how web servers work? Install one and then write some basic HTML.

The wonderful thing about Raspberry Pis in particular is that it is *very hard* to actually ruin them. There are no moving parts, there’s nothing on the board that can be ruined permanently except by physical damage – like literally snapping the board in half – or somehow running an enormous amount of electricity through them and frying things. So if you get it into an unworkable state you can either putter around to figure out how to fix it or just wipe everything and try again.

SCDS: Please tell our readers about the Archivist’s Friend. Do you have any plans for more quirky gadgets and/or passion projects?

JF: The Archivist’s Friend is a little device I’m working on that has a small e-ink screen, like an e-reader, can do wifi and bluetooth, can be programmed in Python and has a little sensor hanging off it that detects both CO2 concentrations and volatile organic compounds. It can sense the total amount of compounds in the air and plot it on the e-ink screen. Because it doesn’t need continuous power to run – the display will remain visible whether or not the device is actually drawing power – it can run off a battery for a good long time.

If you have an archive, and that archive has material that is sensitive to organic compounds – particularly acetate film, which can degrade and give off acetic acid, aka vinegar. It’s called Vinegar Syndrome, and it is highly communicable – you have one reel of film that starts to degrade and it can infect others. I’d like the Friend to, say, be stuck to the side of a film drawer – it has little magnetic feet – and be able to both display the total organic compound level on the screen and also send an alert via wifi if it gets above a certain level.

I still have to knock out some details (right now it can display a numeric level of VoC and send a message, but I would like something a little bit more visually informative, like a line graph) and due to the pandemic I’ve been testing it at home with actual vinegar and so has not been tested in an actual archive, so I’m trying not to think of new projects until maybe I fix both of those issues.

about their life beyond work. Tell us something interesting about yourself—anything you like.

JF: I’m always incredibly bad at these sorts of things. No idea what is interesting about me. Things I find interesting probably look ludicrous to everybody else. Example: I really, really like potatoes. Not only to eat but I like the way they feel In your hand, they’ve got a pleasant heft, like a good rock, but they are also an *organic* thing. Plus there are *so many different kinds of potatoes*, and you always think of a potato as a thing that has been everywhere, but they come from Peru originally? See, bored already, aren’t you?

If you’d like to discuss digital scholarship, schedule a consultation with John, who can be reached via email at jfink@mcmaster.ca. We will also make a recording of John’s upcoming workshop, “LaTeX for Human(ist)s,” available on our Online Learning webpage.

Leave a Reply